Obituaries

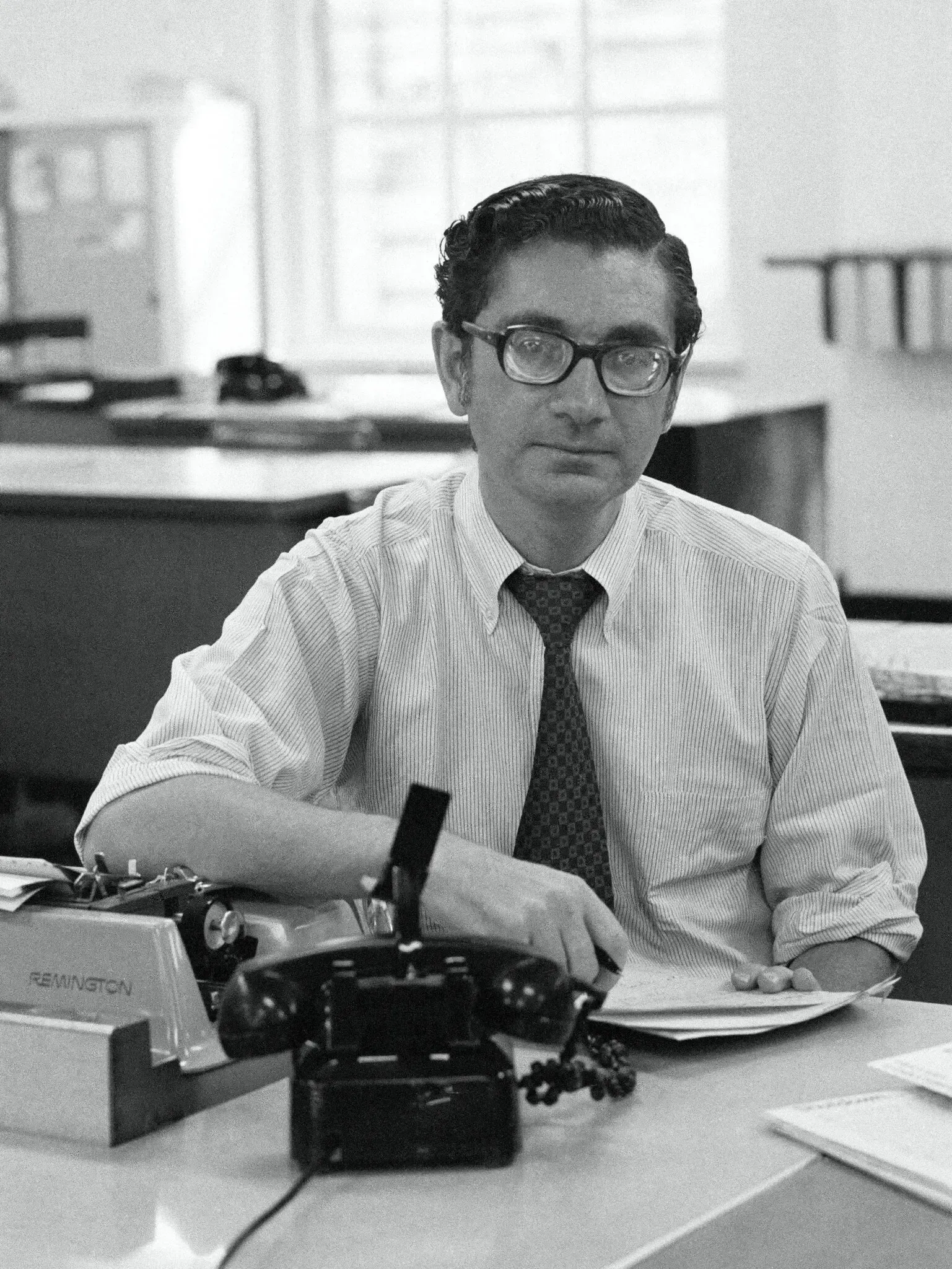

Top Editor, True-Blue Silurian, July 5, 1933-June 1, 2025

The Pulitzer Prize-winning correspondent and former Executive Editor was the public ideal of a New York Times man: polished, erudite and well spoken.

Author, Actor, Politician, All with Irish Flair, 92

Village Voice Co-Founder, Publisher, Soldier, Psychologist, 100

Iconoclastic Reviewer of Our Most Popular Medium