E. Jean Carroll

E. Jean Carroll vs. Trump: Nerve, Not Bravery

By Mel Laytner

E. Jean Carroll doesn't do brave. “It's just nerve," she insists.

Nerve, an abundance of it, is what Carroll needed to sue Donald Trump for sexual assault and defamation, a decision that would eventually result in two jury verdicts totaling $88 million.

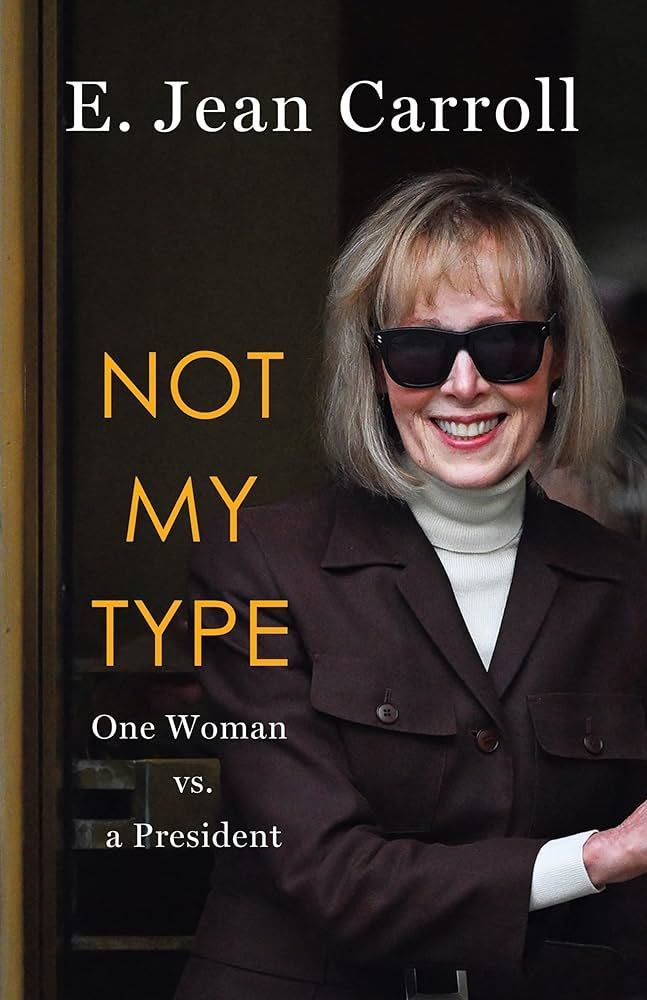

In Carroll’s depiction, her memoir, Not My Type: One Woman versus a President, is more a masterclass in nerve than an epic tale of revenge.

Speaking to an overflowing Silurian luncheon on Jan. 21 with journalist Molly Jong-Fast, Carroll traced the unlikely path from attack to courtroom victory, crediting an unexpected conversation with George Conway, coincidentally at one of Jong-Fast's parties.

In June 2019, Conway had written an article in the Washington Post supporting Carroll’s charges. At the party, Carroll approached Conway to thank him. "He said, I think you could, you could sue Donald Trump," Carroll recalled. Conway took the time to explain to "a nincompoop the difference between a civil trial and a criminal trial. I had no idea. And he said, ‘you could win a civil case. You could win.’ And so that's what did it."

Asked how she endured the barrage that followed—the threats, the police checks, the daily abuse—Carroll was characteristically blunt. “I don’t give a fuck,” she said. “You pay a price. I understood. I was going to pay a price…I don’t care if they kill me—You have to go into that with that kind of philosophy. You cannot care.”

However, it became starkly clear to Carroll's legal team, led by attorney Robbie Kaplan, that it would take a lot more than nerve to win. Before trial, Kaplan conducted mock trials with 27 paid participants to test the team’s arguments. The results were devastating.

All 27 mock jurors believed two people could end up in a Bergdorf Goodman dressing room together. All 27 believed something sexual could happen there. All 27 believed those two people could be Donald Trump and E. Jean Carroll. "What we found out is people thought that I wanted it because he was just too cool and I was too old."

The strategy was clear. Kaplan’s first instruction after the mock trial: “Cut your hair.” Carroll recreated herself as she had been at the time of the assault—same hair, same clothes, same makeup.

“An abuse and a rape case is always about the body of the woman,” Carroll said, “always about the body of the woman.”

Did the daily grind of the trial undermine her confidence? “Oh, yes, of course,” Carroll said. “I feel ugly. Ugly, ugly, ugly, ugly.” Misogyny, she noted dryly, “is back.”

Carroll dealt with the daily attacks by documenting everything each night after court, pacing her hotel room, recording every detail she could remember into her cell phone. “How am I not going to write that book?” she said. “I had every piece of material.”

Despite her gleeful recounting of courtroom absurdities, the mask slipped when an audience member asked what effect the sexual assault had truly had on her. Without hesitation Carroll replied, “No, I never had sex again after that (sexual abuse) in the dressing room. That was the effect.”

There it was: stark, unvarnished truth that cut through her usual devil-may-care persona. After a heavy pause, Carroll said writing her book, “was the greatest therapy in the world. And I am freed, and I feel wonderful.”

St. Martin's Press guarded the book’s publication so carefully that Carroll herself "could not get a copy of this book. They kept it so under wraps because they wanted to spring it on the world." The secret was so well-kept that even Jong-Fast was surprised when Carroll appeared on Morning Joe to announce it.

When Jong-Fast asked if there would be a post-Trump life for them, Carroll pivoted to the subject of her next book, artificial intelligence. "We're very close to artificial general intelligence," which she said would mutate to super intelligence within weeks.

“Don’t worry about Trump. Worry about super intelligence. Trust me.”

---

Mel Laytner, a Silurians board member, was a reporter and editor of hard news for 20 years, much of it covering the Middle East for NBC News and UPI. He is author of the acclaimed investigative memoir, What They Didn't Burn.