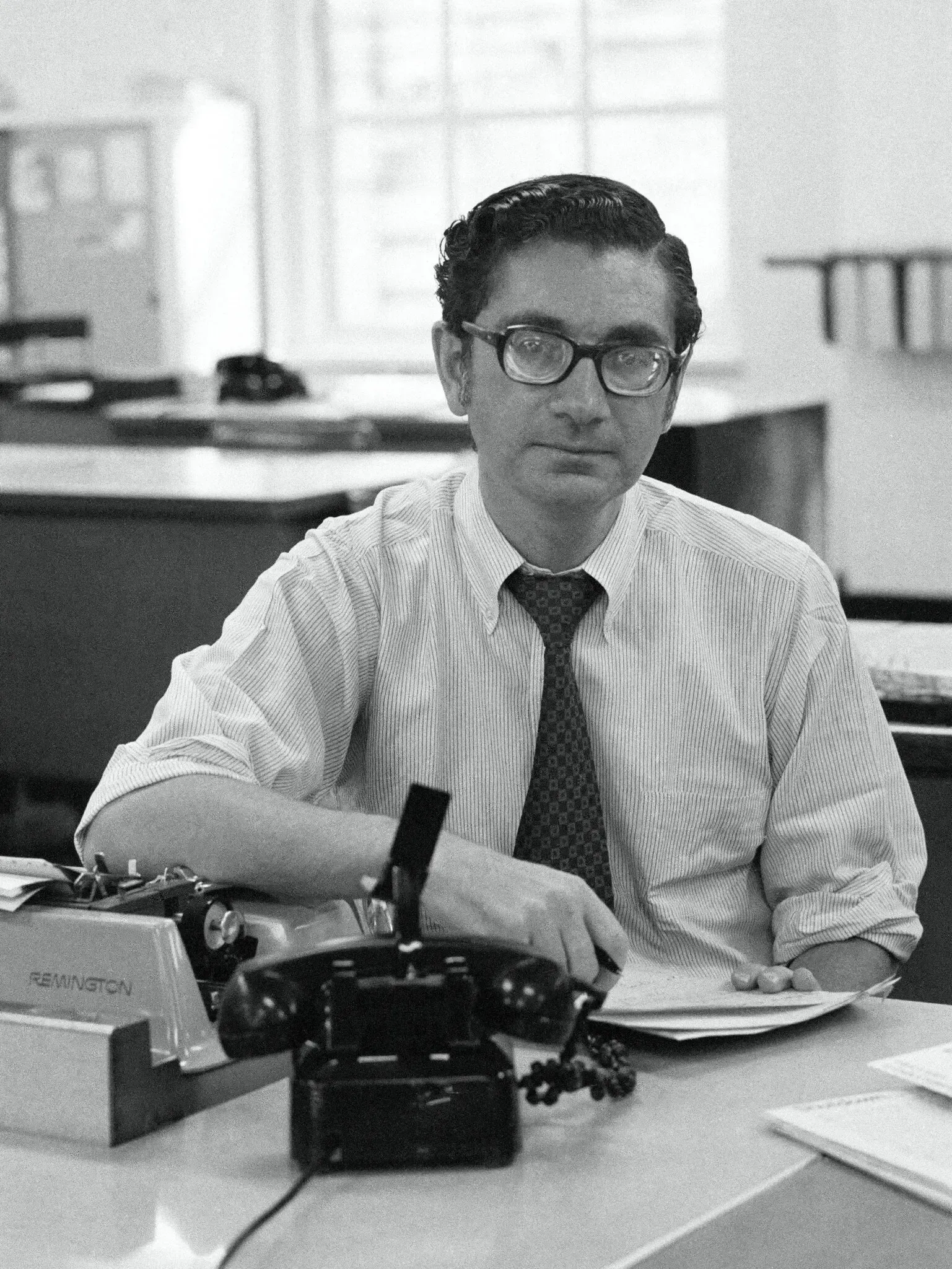

Max Frankel

Fiercely Intelligent, Courageously Honest, Judicious

It was an article that Max Frankel was destined to write.

On Nov. 14, 2001, in a special section marking the 150th anniversary of the New York Times, an article by Max-- as everyone knew him—chronicled in disturbing detail how the Times had buried news of the mass killings that composed the Holocaust in its inside pages or in absurdly short reports. He called the Times coverage the “the century's bitterest journalistic failure.”

It was breathtaking that a former executive editor of the Times would pen such a piece and it was to the credit of the Times and the Sulzberger family that it could so publicly admit its failure and explain its cause: the reluctance of the paper’s Jewish publisher during the war years to appear to be making a special pleading for Jews.

Yet it was standard Max—fiercely intelligent, courageously honest, yet judicious. He had the stature, credibility and compassion to carry off such an assignment even as it must have pained him more than a little to take to task the organization that had been the home of his stellar fifty-year, Pulitzer Prize-winning career.

But as a person with strong principles, Max, who died March 23 at the age of 94, must have seen exposing the Times’ miscarriage as unfinished business, a long-needed correction required by his unsparing code of journalistic candor.

Of course, it was no random circumstance that it was Max who had written the piece. His life had been shaped by the Holocaust. He fled Nazi Germany with his mother and as a 9-year-old settled among other refugees in Manhattan’s Washington Heights neighborhood. For seven often lonely years he did not see his father, who had been trapped in Poland by the outbreak of war and then sent by the Soviets to a Siberian logging camp on the trumped-up charge of being a German spy. Max never saw his grandparents again.

Years later, this ordeal must have made him acutely sensitive to the way his staff might be shaken by the slings and arrows of a life in journalism. As executive editor after the transformative but tumultuous reign of Abe Rosenthal, he infused more kindness and decency into the Darwinian tensions of a newsroom.

At Max’ shiva, his wife, Joyce Purnick, another Times alumnus, recalled that her first encounter with Max came soon after he took the helm of the paper and she received a “herogram” for something she had written. She was elated, though she soon found out many other reporters had received such valentines. Max was signaling that the temperature of the newsroom needed warming.

It was no small matter that Max as executive editor also enhanced the journalism of the Times. He told Metro reporters in the boroughs or suburbs to cover their beats as foreign correspondents might, spurning stories of only parochial interest for those that anyone anywhere might want to read. He urged writers to get to the main point by the fourth or fifth graph, reflecting his impatience with long-winded anecdotal leads that did no favor to the straphanger manipulating a broadsheet on a crowded subway.

He brightened the front page with stories that emerged from the arts and style staffs that revealed meaningful changes in how people managed their lives. And with 24-hour cable television getting the hard news out almost instantaneously, he often gave preference to interpretive versions of a story over the straightforward headline version.

In many ways Max was the public ideal of a Times man, polished, erudite and well spoken, but he loved a good joke and responded with a hearty laugh. At home, he liked to sing—in high school he even contemplated an opera career but gave it up, he wrote in his memoir, because "I may be another Richard Tucker. But if not, or if something goes wrong with my throat, I'll spend my life singing at weddings and bar mitzvahs." He was also a talented painter, reigniting a childhood pastime by taking up watercolors in his last decades. Most of all he loved spending time with Joyce, at their Upper West Side apartment or at their Fire Island beach house, and with his three children and six grandchildren.

“He was a father every day,” his son Jon said of him.

Blessed with a deftly analytical mind, Max could be intimidating as he questioned editors or reporters about stories they were pitching. Yet he was a genuine listener and open to changing his mind. He urged the adoption of Ms. as an honorific and, strove, though not always successfully to diversify the newsroom. He insisted that the Times use the word gay without quotation marks and, as Adam Nagourney wrote, encouraged Jeff Schmalz, who told Max he was gay and had AIDS, to “bring his particular perspective to covering the epidemic.”

The newsroom that emerged fostered freer, even incendiary conversation between the so-called “Blue Wall”—the masthead editors—and the staff. As Todd Purdum wrote on the Facebook Times alumni group the “climate of fear” dissipated.

“When he took over the 43d Street newsroom, it was as if the windows had been thrown open and a gentle breeze had blown In,“ Purdum said.

When the Times decided to publish the name of the victim who accused William Kennedy Smith, a nephew of Senator Ted Kennedy of raping her, many reporters voiced their outrage. Max stuck to his guns, arguing that NBC had already published her name, but he allowed for dissenting voices to be heard. Nagourney said the confrontation was unthinkable in a pre-Max era.

In private or online remarks, reporters spoke of how they always felt liked by Max, that he not only appreciated their hard work but let them know by his banjo eyes and generous smile that he liked them as people. They also singled out his integrity.

I especially like a story Terry Smith told. In the early 1970’s Henry Kissinger, then national security adviser to Richard Nixon, summoned Max to his West Wing office to complain about the supposed inaccuracies in a story by Smith. Max, then the Washington bureau chief, said he would only go if Smith came along. He would not go behind a reporter’s back. At the meeting, Max, puffing on a pipe, allowed Kissinger, a fellow refugee from Hitler, to fulminate. But when the Kissinger resorted to conversing in their shared language of German, a language Terry did not know, Max, signaled that he was on to Kissinger’s stratagem.

"Henry, this meeting is over!” Max said with a chuckle.

Even Kissinger had to laugh.