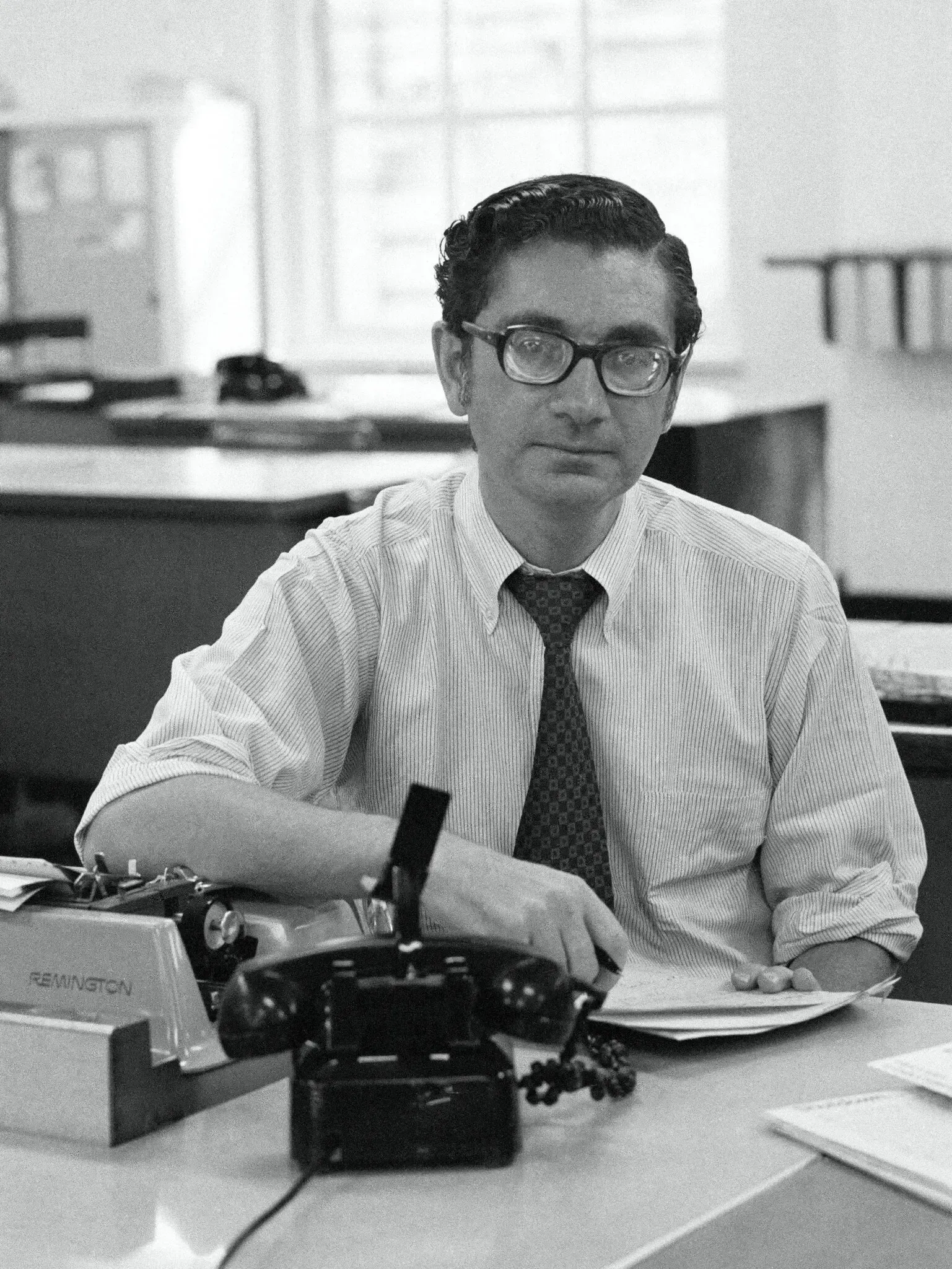

Ed Flancher

Village Voice Co-Founder, Publisher, Soldier, Psychologist, 100

Courage – that’s the quality I first think of when I remember Ed Fancher, who died last September (2023) at the age of 100. Sure, there were a great many things to admire about Ed. After all, he was a man of many parts.

Along with Dan Wolf and Norman Mailer, he had been one of the founders of The Village Voice in 1955 and then had served as the paper’s publisher for the next 20 years. He was also, during his years at the Voice as well as for decades afterwards, a practicing psychologist.

Perhaps it was his training as psychologist that helped make talking to him such a pleasure; his eyes would fix on you with a deep and genuine interest and he always listened with a polite attention. And he was a tweedy, elegantly handsome man; he cut quite a figure in his bachelor days in the Village before his marriage to Vivian (who died in 2020) and his becoming a father to Emily and Bruce.

But for me, it was his courage that always filled me with respect and a large measure of awe.

Ed’s courage was, in one very large part, nothing less than sheer bravery. Raised in upstate New York, he had attended the University of Alaska largely because he liked to ski. But when World War II broke out, he joined the Army and, because of his prowess as a skier, found his way to the elite 10th Mountain Division. The unit was thrown into combat in the snow-covered mountains of Northern Italy. Much of the fighting was hand-to-hand, and Ed made his way through it all resigned, he told me, that he would never come out of it alive.

He didn’t like to talk about the war, but there was a photograph in his study in his penthouse apartment on 11th Street that caught my attention and, when I pressed him, he shared a story. It was a photo of a rifle-carrying Ed in combat fatigues standing alongside two partisans. As Ed matter-of-factly explained, the three were a scout team that had made their way up the seemingly insurmountable rocky cliffs of Riva Ridge in the dead of night. And it was their daring reconnaissance that provided the intelligence which enabled the 10th Mountain Division to launch a successful surprise attack against the Germans encamped in the Po Valley. And Ed, despite the risk, had led the way — once in the recon mission, and then again in the attack.

But Ed also had a moral courage, too. In the Sheridan Square office of the Voice (where I had first met him) he shared an office with Dan Wolf, and together the two men formulated the paper’s guiding philosophy. It would be a writer’s paper, a paper that would speak the truth to power, and also let its writers share their thoughts and ideas, no matter how divergent, from the mainstream. It took a great deal of courage to do this back then, just as this sort of no-holds-barred journalism requires a great deal of courage now, too.

But Ed never backed down. Not in war. And not in peace. He was a man of honor, and he will be missed.

Howard Blum is a former staff writer for the Village Voice who, after working as an investigative reporter at the New York Times, went on to write several bestselling books. “When The Night Comes Falling: A Requiem for the Idaho Student M